In Aleppo one is not awakened early in the morning by the cheerful chirp of a robin or a wren, nor by the clear call of a cardinal, but rather by a penetrating voice crying in Arabic under the window, “Hellu Haleeb”. This syncopated wail persevering on the interval of a minor third defies all sleep. Eventually it lures one to come outside and buy “nice sweet milk” direct from cow to consumer, for the gentle jersey waits at the door bedecked in her blue glass beads.

Breakfast is complete when the little old hunchback man comes along carrying twisted bread rings on a long stick. He sings a chromatic tune from “d” to “f” in dotted eighth and sixteenth notes, “ka-ka-ka-kaak”.

A very few minutes later, a donkey passes by laden with luscious ripe tomatoes. The donkey boy shouts his produce, “banadura, banadura,” just as we would sing “Hallelujah, Hallelujah” from Handel’s Messiah.

Another ambitious merchant with a voice like a sliding trombone does his best to attract the attention of the Syrian housewife to the saddle bags on his donkey. They bulge with shiny black eggplant. His cry begins with a pianissimo effect, makes a steady crescendo, and ends with a soft echo, “Aswad beidenjan, aswad.”

Here is the scissors grinder. He might play the oboe in our street symphony. His private theme is a major second from “D” to “C”, just two long whole notes. He never varies the slightest from this pitch.

The garbage man rings a huge dinner bell. A little boy sitting on the back of the garbage wagon thumps his knuckles against an old tin oil can in a haunting rhythm. If one could be temporarily deprived of smell and eyesight this weird garbage drum would suggest to the imagination a beautiful setting on a stage with kings and princesses marching in stately oriental splendor.

Down in the old copper “suk” or market, there are cymbals enough for all of the symphony orchestras in the world. The cacophony is deafening as the coppersmiths beat out plangent chords upon the huge cooking utensils which they are modelling. The alluring jingle of castanets is nothing more than the lemonade vendor rattling tiny brass saucers in his hand. In the heat of noon day, this percussion rises to a climax when mobs of people fight for a turn at the public wells, old women, young children, and picturesque Bedouin women dressed in gay gypsy rags.

Sleigh bells? Santa Claus? Donner and Blitzen? No, only a dozen or more donkeys prancing down the street in an “allegro” movement. The mood changes suddenly to “andante” when we hear the soft tinkle of camel bells.

Our symphony is not finished at sunset. In the quiet of the evening, out under the stars, the shepherd boy pipes as he guards his sheep. Surely it is the music of the “Magic Flute”! An Armenian boy struggles with his violin far into the night. Sleep, sleep, there is no sleep. The night watchman strikes his club against the pavement, a reverberating “clunk, clunk” to warn all would-be burglars that he is imminent. Then the steady swish of the street sweeper’s broom clears the air for the opening theme of a new day, “Hellu haleeb”.

Rebecca Decherd. 1935. Aleppo, Syria.

“My mother found music in the everyday sounds around her,” Betsy Decherd Lane told The Aleppo Project about this letter in which Rebecca describes the sounds of the street in musical terms. Ms. Lane lived with her parents and siblings in Aleppo in the early 1930s and with her husband and children in the 1960s. She added, “given the destruction taking place in Aleppo, I hesitated to send this gentle piece, but perhaps we need reminders of what that city was – and what it could be again.”

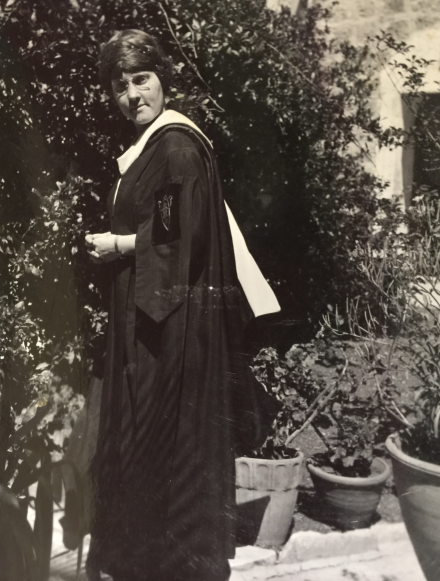

Rebecca Decherd was a graduate of Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Oberlin, Ohio, with a Master’s Degree in organ. Rebecca and her husband Douglas were missionaries, educators and musicians in Aleppo, Syria and Tripoli, Lebanon from 1930 to 1966. In the 1930s, Douglas was the principal at the Aleppo High School which developed into Aleppo College. He later served as principal at the boys and girls schools in Tripoli. Music was an important part of life in the three schools the Decherds served.

The Aleppo Project

The Aleppo Project